12. 71 Fragments of a Chronology of Chance (1994)

An early, and relatively minor, Haneke showing 71 “fragments” – or glimpses of apparently unrelated scenes and people – set in present-day Vienna. These involve a security guard, a troubled young man, a depressed retiree and a Romanian illegal immigrant. So what’s tying them all together? The answer is partially given at the beginning and fully at the end, and the movie gives us Haneke’s keynote themes: the nature of violence, urban alienation, the abolition of compassion and community in capitalism and western hypocrisy in primly looking away from injustice and desolation in other parts of the world. But the backstory twist ending – similar to the one Krzysztof Kieślowski in effect gave us the same year in Three Colours Red – is a bit pat.

11. Funny Games US (2007)

Here is the Americanised replica-remake that Haneke directed himself, a virtual shot-for-shot revival of one of his most sensational and controversial movies. The original from 1997 had a blandly prosperous couple and young son arriving at their handsome lakeside vacation home in Austria and being terrorised by two satanic young men. The remake transplants the action to Long Island, with Tim Roth and Naomi Watts as the couple and Michael Pitt and Brady Corbet as their tormentors. The remake very efficiently reproduces the steely, ice-cold horror of the original. But why duplicate it?

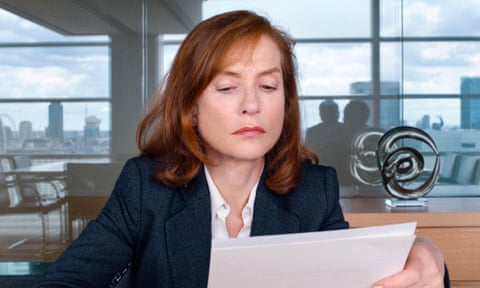

10. Happy End (2017)

A satirical nightmare of haute-bourgeois prosperity, which begins with a video surveillance scene (that key Haneke trope), the screen in mobile-phone-style portrait mode. The scene is a magnificent family estate in Calais, presided over by a woman played by Isabelle Huppert, a key performer and almost-muse for Haneke, brilliant at incarnating glacial hauteur and concealed pain. The family’s wealth is derived from a construction and transport business that cuts corners on safety, and the extended clan gathers in all its dysfunction, a cast including Toby Jones and Franz Rogowski. There are intriguing notes of black comedy in this film, along with the traditional themes of prosperous denial and the return of the repressed.

9. Time of the Wolf (2003)

It can hardly be any surprise that Haneke once made a dystopian post-apocalyptic drama, or that it’s as brutal as anything else in the canon, including The Road and The Last of Us. After an unexplained disaster has destroyed Europe, a woman played by Huppert arrives with her family at their country home where strangers attack them – an unflinchingly shocking and upsetting scene – and she and the survivors trudge away to the train station, where help may be forthcoming. The title is taken from a Norse myth of prehistory, and may also have an echo of Bergman’s Hour of the Wolf. There is a sense of apocalypse in every Haneke film, of course: the film’s certainty that this is what is coming for all of us is very unnerving.

8. Benny’s Video (1992)

This was the early movie that freaked out unsuspecting European film festival audiences and made Haneke a name to conjure with. It also revealed Haneke’s fascination with video and how it made possible a new and coldly tactless scrutiny of our lives, an implacable recording angel of everything we prefer to forget. A disturbed boy called Benny, obsessed with violent images on video, murders a girl and records the act. His respectable parents contrive to cover up the crime, but the video is not amenable to this kind of hypocrisy.

7. The Seventh Continent (1989)

Haneke’s debut feature, intended originally for television, is a stunning, upsetting, faintly hallucinatory drama showing a prosperous middle-class Austrian family realising how empty their lives are and planning to destroy themselves. The initial sequences are composed entirely of closeups on bodily parts: hands, feet, necks, waists, as they go about their daily life. Once we see their faces as well, there are disturbing hints that things are not as they ought to be. There is no full, clear psychological explanation for the domestic apocalypse: just a nihilist horror that gemütlich family life can conceal a profound alienation and despair.

6. Code Unknown (2000)

One of Haneke’s most complex, enigmatic films, constructed on the arbitrary-ensemble model (but more evolved than his earlier 71 Fragments), showing us that things don’t have to add up in the conventional sense. Jigsaw pieces are missing and the audience must exert themselves to engage. Code Unknown is about race, culture, urban rage and alienation, and there are generous, compassionate insights. Juliette Binoche leads the ensemble cast, playing an actor (whose audition as a serial killer’s victim appears at first to be actually happening, flavouring the entire film with fear). There are sensationally painful, uncomfortable encounters, most prominently between a spoilt young man and a young African guy who confronts him about the way he treats a Romanian beggar. Powerfully confident, cerebral, uncompromising film-making.

5. Funny Games (1997)

In the 90s, moviegoers thought they knew all about the “home invasion” horror genre. Not like this, they didn’t. Haneke regulars Ulrich Mühe and Susanne Lothar play a well-to-do couple who show up with their son at their lakeside vacation home, where they are terrorised by two well-spoken young men, played by Arno Frisch and Frank Giering. Funny Games was the film that made Haneke a serious name, and with Von Trier, Noé, Breillat, Reygadas and Seidl, he became first among equals in the new extreme cinema. Funny Games was his ferocious rebuke to Hollywood’s commodified violence that exploits shock value for titillation and middleweight drama. The physical violence here is chiefly off camera: but the real-time, moment-by-moment ordeal of fear and despair is all too explicit. The dreamy Handel at the beginning suddenly being blitzed by death-metal (Naked City’s Bonehead) is one of the great Euro-shock moments.

4. The Piano Teacher (2001)

Haneke’s sole literary adaptation (so far) is from the novel of the same name by Austrian author Elfriede Jelinek, whose dark view on life made her a kindred spirit; and this film may conceivably have helped her win the Nobel prize three years later. It is about the unacknowledged coldness and repression in polite European culture, and features Isabelle Huppert as a supernova of evil and despair. She plays Erika Kohut, a brilliant piano teacher and Schubert scholar whose emotional life is frozen into stagnancy and self-harm. When she conceives a passion for a handsome young student (Benoît Magimel), she tells him that their relationship can only involve him beating her – and there is nothing sex-positive or celebratory about this BDSM. In her severity, mad anger and fear of love, Huppert’s performance is coldly magnificent.

3. The White Ribbon (2009)

One of the richest and most rewarding of Haneke’s later movies (which even has grace-notes of humour) about group-guilt, the poisoned-herd mentality in denying or repressing the truth and the origins of German political behaviour in two world wars. The film is shot in stark black-and-white in an imaginary German village in 1913: an outwardly placid community, but actually dysfunctional, plagued with anonymous acts of malice and spite. Burghart Klaussner plays the pastor, a severe disciplinarian who rules over his family and household with a rod of iron. When his children err, they have to wear a humiliating “white ribbon” around their arm until he is satisfied they have atoned – it is apparently a forerunner to the yellow star and the Nazi armband. There is no clear solution to the mystery, but its sinister riddle is unforgettable.

2. Hidden (2005)

This is another Haneke film about the uncanny world of video, also with an almost Hollywood premise: a celebrated TV personality has a stalker who leaves sinister videotapes on his doorstep showing the exterior of his home. (David Lynch did something similar in Lost Highway.) But this chilling film makes it the basis of a preternatural nightmare and a political essay on France’s imperial guilt, with a final deadpan sequence over the closing credits almost, but not quite, explaining everything. Daniel Auteuil is the blandly conceited TV star fronting a cultural discussion show, Juliette Binoche his wife, and they have a school-age son. Auteuil suspects that the person behind the videotapes is an Algerian to whom he once did something awful, connected with France’s repressed memory of the massacre in Paris in 1961 – la nuit noire – when hundreds of Algerian demonstrators were beaten and killed.

1. Amour (2012)

Haneke’s stark treatment of mortality and fear arguably revealed a new strain of compassion and forgiveness in him in this intimate domestic drama. Jean-Louis Trintignant and Emmanuelle Riva play two retired music teachers, Georges and Anne, a married couple who live happily enough in an elegant Paris apartment. But when Anne suffers two strokes, she makes her husband promise that he will never put her in a home. When he is obliged to look after her without institutional palliative care, it becomes an ordeal in which all they have is their love – and perhaps even that is being dismantled as Anne’s identity is eroded. Their love is real; it may not be a consolation, but it is the only thing that gives their fragile lives meaning.