- India

- International

How writer Moin Beg’s story about Lahore’s courtesans prompted Sanjay Leela Bhansali to create Heeramandi

Writer Moin Beg on how the world of Lahore’s courtesans and their crucial role in the Independence struggle led him to write the story of Heeramandi and the two decades it took before Sanjay Leela Bhansali brought it to life.

Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi is streaming on Netflix.

Sanjay Leela Bhansali's Heeramandi is streaming on Netflix.Moin Beg was about seven when he first heard the term ‘Heera Mandi’ in his plush living room in Mumbai’s Byculla – a cultural and industrial centre in the ’60s. His parents, who shifted from Lahore post the Partition, were hosting a soiree for the city’s cultural elite. Beg remembers how his home, where he still lives, throbbed with mushairas and musical performances.

Regulars among the guests included famed musician Suraiyya and Mallika-e-ghazal Noorjehan, the leading lady of the time, Nargis, Jaddan Bai’s daughter whose versatility was the talk of the tinseltown and Ustad Bade Ghulam Ali Khan, the torchbearer of Kasur-Patiala gharana. While many elders from the family feted these women famous in the Hindi film industry, there was a lot of hushed chatter when their backs were turned. “Ye toh sab kanjriyaan hain Heera Mandi ki (These are all Kanjaris of Heera Mandi),” they’d say derisively. ‘Kanjari’, which meant ‘a woman from the Kanjar community’, usually used for craftspeople and entertainers, was used as loosely interchangeable with a prostitute.

“I have been intrigued by these women since childhood. Not only were they beautiful, they were also extremely talented and accomplished singers, dancers and poets. I would ask my mother, what is Heera Mandi? What is Kanjari? And was promptly asked to shut up and not talk about it,” says Beg, 66.

Beg’s fascination led him to a fact-finding expedition to Lahore during his visits to his family home in the walled city. It included conversations with several family members besides reading books and papers on Heera Mandi’s courtesans. That the remnants of a time gone by existed still, however ghostly, helped.

Also Read | Heeramandi review: Part history, part myth, full-on Sanjay Leela Bhansali

Beg’s research has culminated in the original concept of Heeramandi: The Diamond Bazaar, director Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s latest venture on Netflix. Part history, part fiction, and part Bhansali’s overarching opulance, it’s the story of three generations of courtesans against the backdrop of the Independence struggle and stars Manisha Koirala, Sonakshi Sinha, Aditi Rao Hyderi and Richa Chaddha among others. Set in Lahore’s Heera Mandi, a now-defunct red light district, which was once the famed Shahi Mohalla dazzling with culture, courtship and the music and dance, this is where the courtesans lived — women with financial and social autonomy, who were adept at and respected for classical music, dance, literature, politics and the art of conversation and seduction.

Sonakshi Sinha as Fareedan, Manisha Koirala as Mallikajaan in Heeramandi: The Diamond Bazaar. (Photo: Netflix © 2024)

Sonakshi Sinha as Fareedan, Manisha Koirala as Mallikajaan in Heeramandi: The Diamond Bazaar. (Photo: Netflix © 2024)

Established by the Mughals, the area was originally a residential neighbourhood for the attendants of the royal courts. Soon, many courtesans from the palaces also began living here. Facing the regal Badshahi Mosque, Lahore’s most iconic landmark, and near Taxali gate, which once stood next to the bazaar, the name Heera Mandi came about in18th century, after Hira Singh Dogra, Prime Minister of Lahore under Maharaja Ranjit Singh’s reign started a grain market here. The term fit the bill for women from the kothas too. And for years nawabs, rajas and their sons came to learn adab (etiquette), nafasat (refinement) and shaistagi (how to be respectful), as Qudsia Begum (Farida Jalal) mentions in a conversation in the series. At a time when many women were quite subservient in domestic spaces, these were women who could speak confidently about politics, literature, and offer fine repartee.

“Both sides of my family are Mughals. My grandfather, my father who was a poet himself, everyone customarily went to the tawaifs. So the stories were always there,” says Beg.

His father, Hakim Mirza Haider Beg, President of the All India Hakims Association, moved to India after then Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, asked him to set up home here. But the family often went back to Pakistan to meet relatives. On one of his visits in the ’80s, Beg’s mother asked him to give some money to a young family friend who had lost her husband and was now teaching the children of the courtesans on the outskirts of Heera Mandi. “She gave me the larger picture besides introducing me to some of the tawaifs,” says Beg.

Also Read | Heeramandi: Enough with celebrating ‘tawaifs’ and ‘kothas’, there’s nothing to applaud in non-consensual sex

From these women, Beg heard of stories of the older times, how these professional women musicians, often shrugged off contemptuously for practising the oldest profession in the world, were also the unsung heroes of the Indian freedom struggle. That’s when he decided to write their story.

“By the ’80s, decadence had set in. Heera Mandi had lost its sheen and many courtesans were dancing to cheap Hindi film songs. But, there were still kothas that were focused on classical music. It was quite the irony that the tawaif reigned supreme in Heera Mandi. But once her carriage rolled out of there, she carried a stigma alongside,” says Beg, who was captivated by the dichotomy the tawaifs represented.

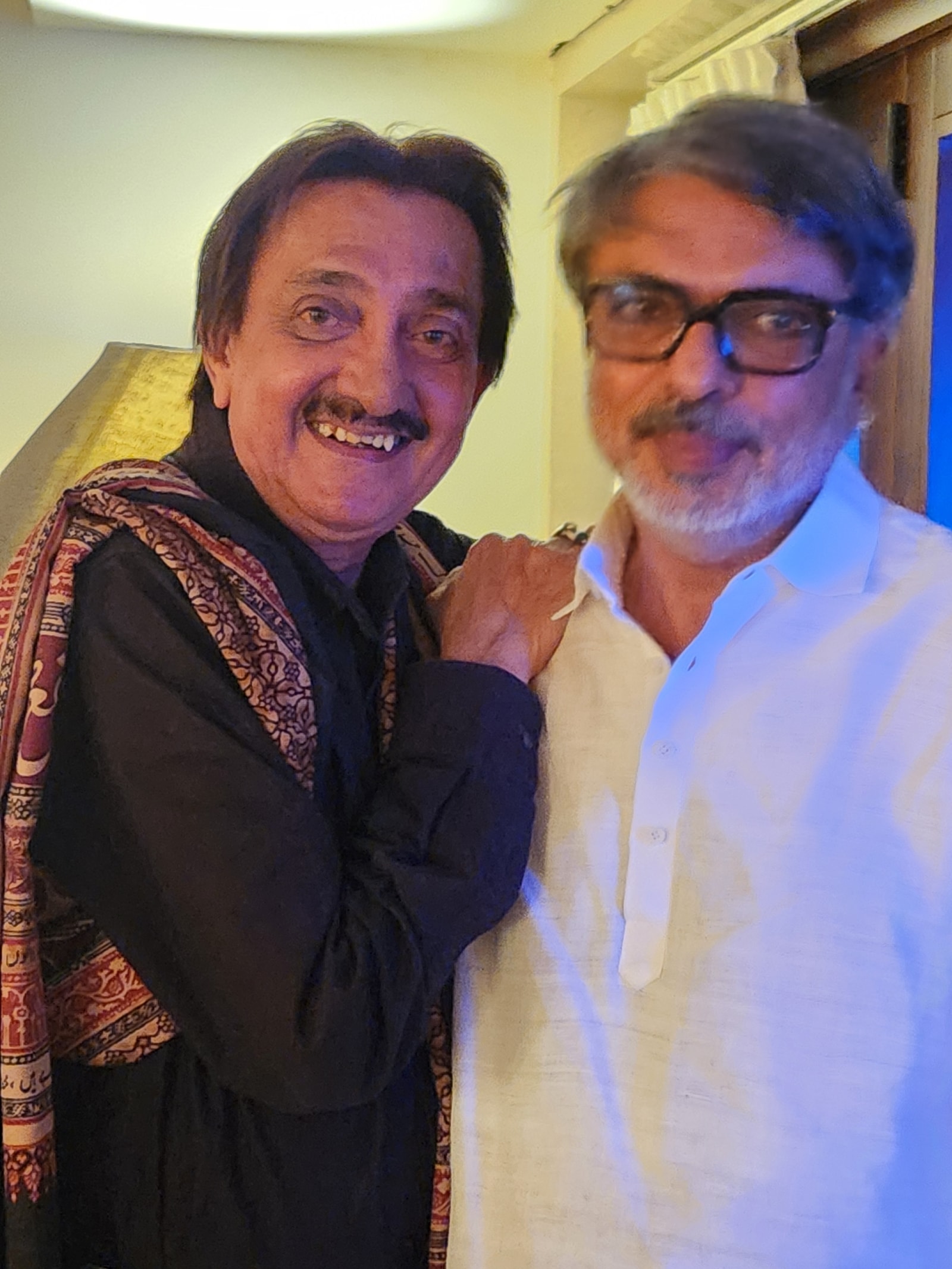

What emerged was a 25-page draft that Beg wrote about two decades ago for a feature film and told his friend and actor Aditya Pancholi about it, who was incidentally Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s neighbour. A phone call later, he met Bhansali for a narration.

Moin Beg with Sanjay Leela Bhansali.

Moin Beg with Sanjay Leela Bhansali.

The filmmaker was keen on searching for these women who had been whitewashed from one’s consciousness as skilled artistes and freedom fighters and were remembered primarily for being involved in sex trade. “It’s a very ambitious and vast project. It tells you the story of the courtesans pre-Independence. They kept the art of music, dance and living,” says Bhansali, in a Netflix interview. In the series, the music, also by Bhansali, features a couple of older bandishes such as Sakal ban by Amir Khusrau and Rasoolan Bai’s Phool gendwa na maaro besides Najariya ki maari from Pakeezah only with a different composition.

Beg had to wait though for years as Bhansali got busy with other projects including Padmaavat (2018) and Bajirao Mastani (2015) among others. “But we kept talking. He kept coming back to the story and we became good friends. After so many years, he would start something else and I would fight with him and tell him to return my script. But he’d say, he will make it someday,” says Beg.

At the premiere of the series last week in Mumbai, Beg says that actor Rekha welled up while congratulating him. “Guzra huya zamaana yaad dila diya (you brought back memories of times gone by),” she said.

May 18: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05